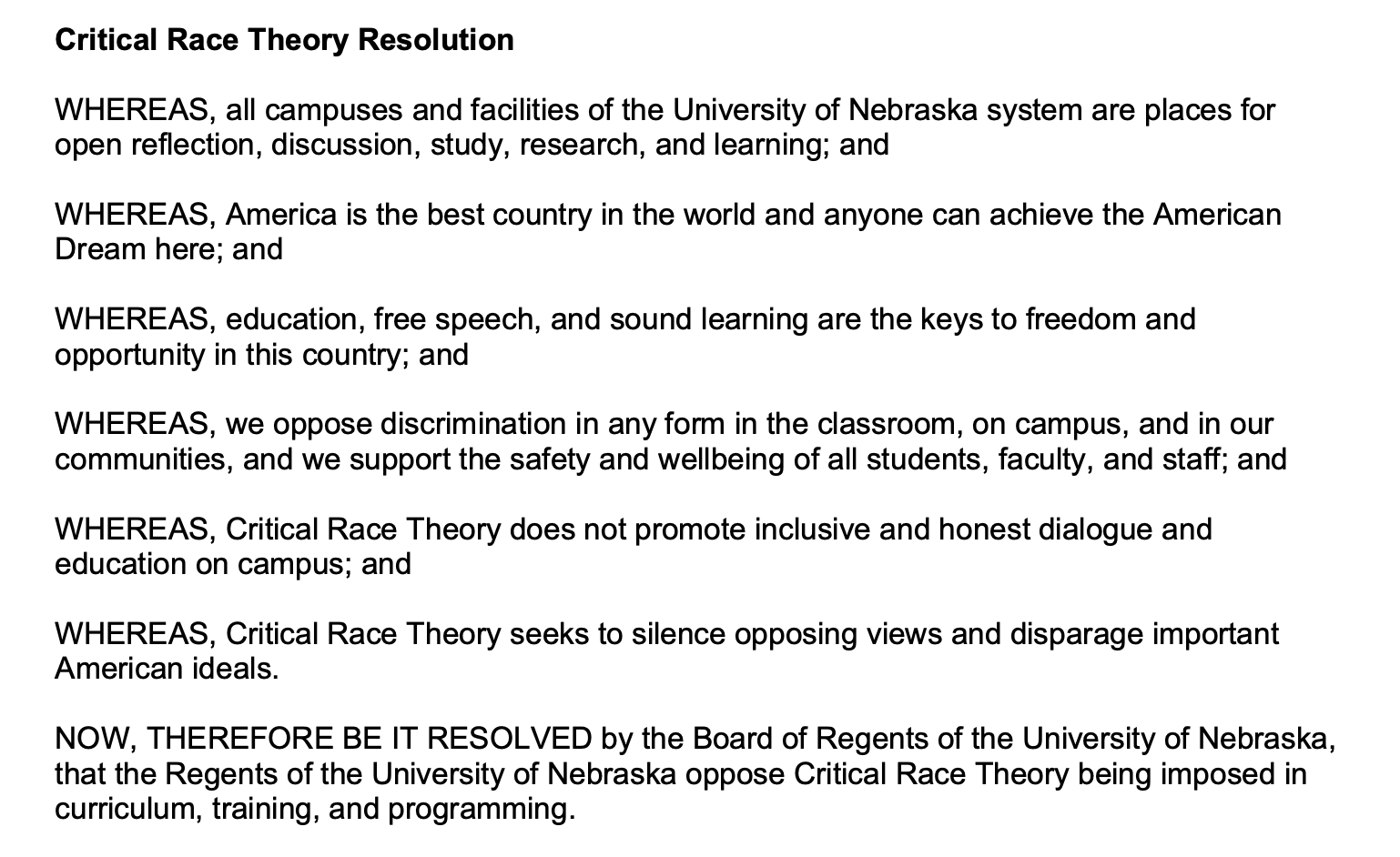

The Board of Regents for the University of Nebraska system on Friday voted down an anti-critical race theory proposal from one of its members. Unlike many states' legislative bans on mandatory critical race theory training, the Nebraska proposal explicitly opposed the "imposition" of critical race theory via the curriculum.

"America is the best country in the world and anyone can achieve the American Dream here," says the resolution, written by regent Jim Pillen. "Critical race theory seeks to silence opposing views and disparage important American ideals" and the Nebraska regents "oppose critical race theory being imposed in curriculum, training and programming."

The 3-5 vote against the proposal followed hours of discussion. Students, faculty members, deans, the board and its four non-voting student members, plus Ted Carter, system president all weighed in. All but a handful of their comments were against the resolution, echoing sentiments of numerous student and faculty groups who opposed it prior to the vote.

Most Popular

Academic Freedom at Stake

"It might be critical race theory today, but tomorrow it's another topic that is deemed un-American," Caleb Hendrickson, an undergraduate at Nebraska's Kearney campus, told the board during the public comment period. "I stand before you all as a student of UNK. But deeper than that, I am a kid from rural Nebraska, one of thousands in our great state, who has been able to learn freely through our public education system since I was 5 years old. I hope that you all can see the importance of maintaining the integrity of our education as history tells us, rather than our government dictating what we can and cannot hear."

Jeannette Eileen Jones, associate professor of history and ethnic studies at the flagship Lincoln campus, said it's "disingenuous" to paint discussions involving critical race theory or race in general as divisive or anti-American.

Jeannette Eileen Jones, associate professor of history and ethnic studies at the flagship Lincoln campus, said it's "disingenuous" to paint discussions involving critical race theory or race in general as divisive or anti-American.

"We are not in the business of teaching lies about the history of the United States or any other history in the world," Jones said. "What we want is to empower our students to critically think about history, and one of the things that we have to talk about is the history of ideas, race, gender, sexuality -- whatever ideas have come into our political thinking. Our intellectual history has to be debated."

Absent that kind of debate, Jones said, "we are treating our students as if they're infants and children."

Regina Werum, professor of sociology at Lincoln and outgoing president of campus advocacy chapter of the American Association of University Professors, told board members it's their "responsibility to respect and protect the institutional mission." When "we all tell you the same message, maybe you'll listen," Werum continued. Critical race theory "is not an ideology. It's a theory. It's part of our toolbox. Saying anything else means you're misrepresenting it to the public, and you're being disrespectful of your faculty. Please listen to us."

Carter, who previously opposed the resolution in a public letter signed by all four Nebraska campus chancellors, told the board that critical race theory, among other ideas, is being presented to students in some courses. But it's "not being imposed on students at the undergraduate, graduate or the Ph.D. level at the University of Nebraska," he said.

'Trusting' Students and Faculty

The resolution also "gives a perception that we don't trust our faculty," he said. "We have to support academic freedom."

Related Stories

Pillen, a Republican, is currently running for governor to succeed another vocal proponent of the resolution, Republican Governor Pete Ricketts, who is term-limited. Pillen said prior to the vote that his resolution had a "clearly defined scope and mission, to prevent this institution from imposing extreme ideologies that a majority of fellow Nebraskans find to be discriminatory, divisive and the polar opposite of how we live."

Other board members disagreed, saying that the scope of the proposal remained undefined, and its purpose, problematic. Regent Elizabeth O'Connor, who voted against the proposal, said, "I asked in committee for certain terms in this resolution to be clarified because I felt it was too vague to make sense. But I suppose that was the point -- it left just enough space to be able to defend itself."

Regent Timothy F. Clare, who also voted against the proposal, said "we're being asked to take unprecedented action as a board. We're being asked to consider a policy that has the perception, and potentially the reality, that in effect limits what students at the University of Nebraska can or cannot learn as they pursue their education."

Multiple members of the board commended the room and their colleagues for being able to hold a lengthy discussion about a contentious issue. Carter, the system president, said, "The nation is watching us today. To my knowledge, no publicly elected board has taken this topic up. There's been 20 states that tried to legislate critical race theory away, but nobody's had a real meaningful dialogue."

Damage Done

The discussion was not without tension. Multiple student commenters accused Pillen of crafting a proposal about something he didn't really understand to forward his political campaign, not the university mission.

Some students and graduates of color also said they felt hurt or disappointed by the board's serious consideration of a proposal seeking to limit discussions of how race impacts life in this country. Critical race theory, which emerged from critical legal theory decades ago, centers on institutional, not individual, racism.

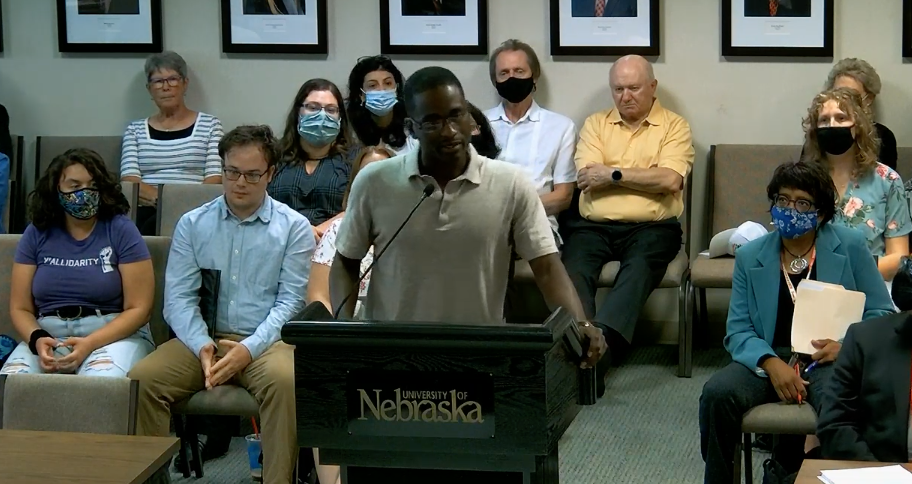

Ibraheem Hamzat, right, a 2020 Black graduate of the Lincoln campus and second-year medical student at the University of Chicago, said, "The thing that pains me the most is that deep down you know this is meaningless. You know that American history requires us to consider critical race theory. You cannot consider American history without considering the ways in which the legal system has impacted Black and Brown and Indigenous people in this country."

Hamzat said his medical interests were inspired in part by a course he took at Lincoln, which used critical race theory to examine documented health outcome disparities among racial groups in the U.S. He told Pillen, directly, "I think that if you'd taken this class, you probably would not have written this resolution."

Hamzat said his medical interests were inspired in part by a course he took at Lincoln, which used critical race theory to examine documented health outcome disparities among racial groups in the U.S. He told Pillen, directly, "I think that if you'd taken this class, you probably would not have written this resolution."

Even as the board voted it down, some in Nebraska continued to feel that it had done serious damage to the university.

Julia Schleck, an associate professor of English at Lincoln who wrote about the resolution for the AAUP's Academe blog, said she was "extremely proud to hear the voices of our students come out so strongly against this resolution."

One might say that the "attack on the university's academic freedom and commitment to studying race and racism unified us and inspired us to assert our values," she added.

At the same time -- and despite the optimistic regent statements about the tenor of the debate -- the discussion "has not strengthened the university," Schleck said. "It has clearly demonstrated that some of our leaders on the board do not actually understand how to protect academic freedom, despite their invocation of it. It has already, and in spite of the vote count, damaged our ability to recruit and retain the best students and faculty from around the country and the globe." And it's damaged trust that egents will act with "integrity in their role, attending to the best interests of the university."

Especially for scholars who teach about race, Schleck added, "the episode as a whole created a chill that will be hard for those faculty -- all of us, really -- to shake off."

Nuri Heckler, an assistant professor of public administration who researches whiteness and masculinity, said the vote allayed concerns about his ability to stay in Nebraska for the foreseeable future, since his work requires that he teach critical race theory. That work was challenging even before the resolution debate, he also said, as "it's never something that's comfortable, especially for white students. Some do tend to push back in the beginning."

Knowing now that there are "people who are out to sort of try to catch you doing something that is controversial -- that's definitely going to have a bit of a chilling effect for me," said Heckler, who is white. "I'm just going to have to go forward and do it anyway. But I do fear for especially my colleagues of color, and how this will affect their ability to teach."

The regents' vote did do one concrete thing: put the Lincoln campus back in the good graces of the national AAUP. Prior to Pillen's proposal, the group had been preparing to take the Lincoln campus off of its list of institutions censured for allegations of violations of academic freedom, where it landed following a 2018 incident. But negotiations to get the university off the blacklist halted while Pillen's proposal was pending.

Mark Criley, a senior program officer at the national AAUP, said that the group "will now certainly resume its work with the UNL administration concerning removal of censure. The regents' resolution was the sole reason those efforts were put on hold."

"freedom" - Google News

August 16, 2021 at 02:01PM

https://ift.tt/3iP1w7V

A win for academic freedom in Nebraska - Inside Higher Ed

"freedom" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUAlgg

https://ift.tt/2VYSiKW

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "A win for academic freedom in Nebraska - Inside Higher Ed"

Post a Comment