USA TODAY’s “Seven Days of 1961” explores how sustained acts of resistance can bring about sweeping change. Throughout 1961, activists risked their lives to fight for voting rights and the integration of schools, businesses, public transit and libraries. Decades later, their work continues to shape debates over voting access, police brutality and equal rights for all.

ANNISTON, Ala. – Hank Thomas sensed he was about to die.

Thick smoke billowed out of the shattered bus windows surrounding him, curling in the southern heat. It mixed with a chorus of screams, flung with venom from the mob encircling the marooned Greyhound bus.

Inside, he and his fellow passengers crawled between seats through broken glass, gagging as a gritty soot coated their throats.

Thomas folded his lanky frame into the narrow aisle, sweating through his plaid sports jacket as he tried to think. He was 19. A few weeks earlier, his death had not been entirely conceivable. Now, he wondered, would it come from the flames he felt at the back of his neck, or at the hands of the Klansmen outside?

Maybe he could accept a lungful of smoke.

He took a deep breath.

The Freedom Ride movement almost ended in Alabama on May 14, 1961, when Thomas and six other Riders nearly died on a bus set ablaze in rural Klan country.

Ten days earlier, an integrated group of 13 civil rights activists began their journey to challenge segregated interstate travel accommodations in the South, which held fast to illegal Jim Crow practices.

A journey of nonviolence and direct action in the face of hate, the Riders traveled in two groups on separate bus lines, facing brief violence and arrests as they moved deeper South. The journey descended into hours of vicious violence in Alabama, where federal law enforcement knowingly allowed local police to collaborate with the Ku Klux Klan.

The Mother’s Day bloodshed galvanized a movement. Waves of new Riders poured into the South for months, risking everything to force the country to face the hateful actions upholding unlawful, racist practices.

“I didn’t know anything about fear,” Thomas said. “But I came out of Anniston with a renewed sense of determination.”

Sunday dawned sunny and clear as the Riders headed to Atlanta’s Greyhound and Trailways stations. They split up to take two staggered itineraries into Alabama. The Greyhound would leave first.

Thomas took his seat on the Greyhound bus next to 27-year-old Ed Blankeheim, a white, bespectacled veteran and college student. Genevieve Hughes, a white stockbroker-turned-activist, boarded the bus clutching a book to help pass the drive into Anniston. Mae Frances Moultrie, dressed in a pale, belted shirtdress with earrings shining beneath her chic bob, slid into a fabric seat midway back. Three other Riders sat scattered among other passengers, including two white men in suits, one of whom stored a case in the luggage compartment before climbing aboard.

The passengers exchanged idle small talk as the bus departed Atlanta.

Moultrie, a 24-year-old Black college student who joined the Rides in South Carolina, gazed out the window, watching the Georgia interstate bleed into Alabama countryside. “God, protect us and keep us from injury,” she prayed.

Burning of Freedom Riders’ bus by white supremacists shocked the world

On May 14, 1961, outside Anniston, Ala., Hank Thomas and other Freedom Riders huddled on a Greyhound bus as a white mob threw a firebomb inside.

Jasper Colt, USA TODAY

The Congress of Racial Equality started recruiting Riders in early 1961, nearly 15 years after attempting its first ride through the South. Supreme Court rulings in 1946 and 1960 outlawed segregated seating and facilities in interstate bus travel, but Jim Crow practices still relegated Black people to sub-standard accommodations.

“They weren’t trying to change the laws. The laws had been changed,” said Dorothy Walker, director of Alabama’s Freedom Rides Museum. “They were trying to change the system that was allowing those laws to be flouted."

CORE aimed to train a multiracial, multigenerational group of Riders to carry out their “tests,” such as integrated seating, or sending an integrated pair into a station waiting room.

Organizers feared the deeper South the buses went, the greater the danger. CORE wouldn’t allow anyone younger than 21 to participate without parental permission.

A natural activist from a young age, Thomas joined lunch-counter sit-ins as soon as he arrived at Howard University in Washington, D.C., in 1959. His roommate was originally selected for the Rides, but Thomas replaced him at the last minute after he got sick.

The Riders departed from Washington on May 4. Both bus groups were slated to arrive in New Orleans 13 days later. After they arrived in Atlanta on May 13, rumors swirled about the journey to come. At dinner, Martin Luther King Jr. cautioned Riders they wouldn’t make it through hostile Alabama and Mississippi.

Thomas trusted King’s warning, but it wasn’t enough to stop him.

“It didn’t take much to convince me that we were not going to have a good time in Anniston,” Thomas said. “But there was no way I was going to back out.”

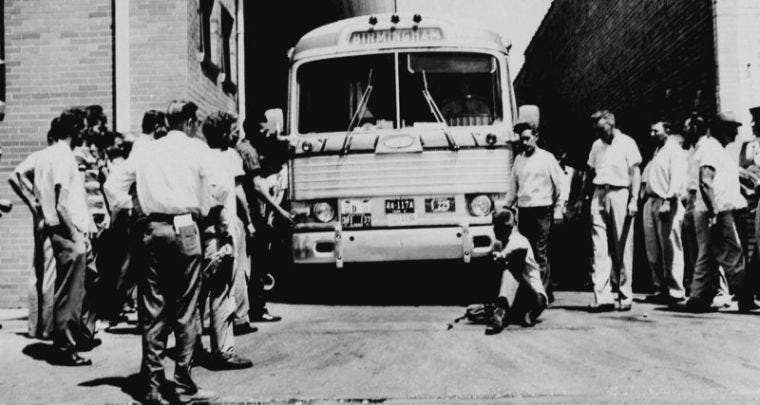

As the first bus pulled into the Anniston Greyhound station just before 1 p.m., Thomas sensed an eerie stillness. The Riders were silent.

A mob appeared all at once.

At least 50 white men, many from Alabama Ku Klux Klan Klaverns, surrounded the bus.

Blankenheim turned to Thomas, motioning for them to get off to test the station accommodations.

“Ed, take my word for it,” Thomas said. “It’s segregated.”

Men began pounding on the bus exterior. Roger Couch, an 18-year-old Klansman, stretched out on the pavement in front of the tires, blocking the bus from moving.

“Communists!” the crowd shouted. “Cowards!”

The two white men seated at the back rushed forward. Unbeknownst to the Riders, the Alabama Highway Patrol had planted Cpls. Ell Cowling and Harry Sims in plain clothes to record the journey through the state.

The two officers now stood inside the bus, staring at their fellow Alabamians – people dressed in their own plain clothes, slacks pressed and shoes shined to their Sunday best – with mounting unease as the mob whipped itself into a red-faced fervor.

Hughes eyed a young man near her window who brandished a pistol as he met her gaze. She quickly looked down at the book in her lap, pretending to read. She wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of her fear.

The mob pummeled bus windows with crowbars and chains and brass knuckles, raining glass on the passengers inside.

Thomas had trouble staying still. It felt like the mob was warming up for target practice. He was the target.

The Riders heard the taunts and slurs. They heard the windows crack and shatter.

But no one on the bus heard the knife plunge into the front left tire.

White terrorists spent weeks preparing for the Freedom Rider’s arrival in Alabama.

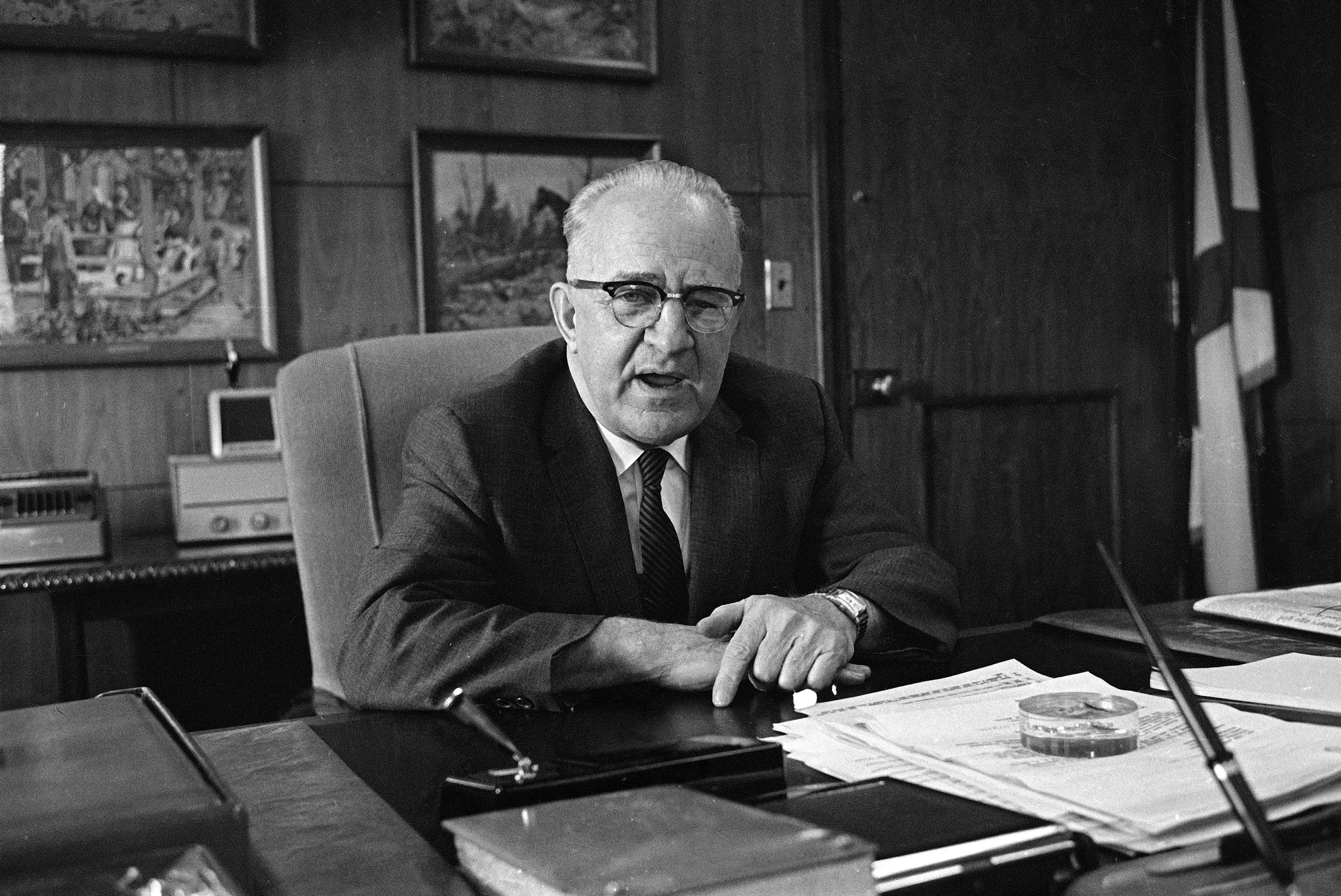

In April, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Birmingham office forwarded intelligence on the Rides itinerary to Birmingham Police Sgt. Thomas Cook. Cook, a Klan sympathizer who worked closely with Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, passed the information on to a well-connected Klan member in the area, Gary Rowe.

City police would allow the Klan 15 minutes in the Birmingham bus terminal when the two buses arrived. No Klan member would be charged, Cook told Rowe.

“Beat ’em, bomb ’em, maim ’em, kill ’em,” Cook said. “I don’t give a shit.”

The FBI knew what the Klan was planning, thanks to their own informant: Rowe. But they did nothing to inform CORE of the impending danger.

Klan leaders looped in Anniston-area Klaverns, suggesting some opening action before Birmingham. But leaders didn’t trust Anniston Klan leader Kenneth Adams, an erratic, violent man, even by Klan terms. They certainly didn’t intend to stop the buses from arriving in Birmingham, where hand-picked Klansmen would be waiting.

“The Klan really didn’t have what happened here in Anniston in their overall plan,” said Theresa Shadrix, a journalist who reported on Anniston-area Klan members before their deaths. “Kenneth had his own rules, his own agenda.”

As the Klansmen continued to break windows and slash tires on the bus, local law enforcement moved, albeit slowly. Anniston police sympathized with the mob, but had not fully collaborated with them as in Birmingham or given them carte blanche for destruction. Police, eager to get the bus out of their jurisdiction, cleared a path for them to leave town after about 20 minutes of destruction.

Any relief Thomas felt faded as he watched vehicles slinking behind them past city limits. At least two swerved in front of the bus, blocking its path to a speedy exit.

The tire began to hiss about 6 miles out of town.

The driver maneuvered to the side of the highway, running to a nearby store to call for help. Cowling, the Alabama patrolman, rushed off the bus, digging for his pistol in the luggage compartment. Strapping on the firearm, he stood in the doorway.

A mob began to form, pouring out of the trailing caravan. One man took a crowbar to the windows. Others rocked the battered silver vehicle to and fro. Men screamed for the Riders to come out, come out.

“Let’s kill these n-----s on this bus, and these n----- lovers.”

Cowling retreated into the bus, locking the door behind him.

“If you don’t come out, we’re going to gas you out,” a man near the front ranks yelled, pulling a cloth-wrapped bundle from a nearby car. Striking a match, he set the bundle alight and pitched it through a shattered window.

It landed behind Hughes in a flash of smoke. Her calm demeanor began to slip into panic.

“Is there any air up there?” she shouted.

Thomas took a deep breath, ready to die, but his body rebelled when the smoke hit his lungs, desperate for clean air.

Coughing, Thomas forced himself to the bus door.

Two men blocked the exit, yelling through the din: “Let’s burn them alive. Let’s burn them alive.”

One of the bus fuel tanks exploded, forcing the horde backward. Thomas stumbled onto the grass.

“Are you all OK?” a white man said.

Thomas nodded. The man’s face twisted in a sneer.

A bat careened toward Thomas’ head, sending him sprawling. As he tried to stand, Thomas saw someone coming back for a second pass. Instinctually, Thomas reached out for Cowling, grabbing him around the waist.

Cowling pulled his gun. For the second time in minutes, Thomas thought he was about to die and dropped his head in his hands.

Cowling pointed his pistol skyward and fired.

“You’ve had your fun,” Cowling told the mob.

Thomas tried to catch his breath. His lungs felt scalded, his throat seared. Someone pressed a water-filled paper cup into his hands. He looked up at a young white girl, Janie Miller, whose family owned the nearby general store.

“That little girl was doing what she learned in Sunday School, to help somebody in need,” Thomas said. “Those adult Christians were looking at her with fire in their eyes.”

The second bus, which left Atlanta an hour after the Greyhound, arrived at the Anniston Trailways station to news of the initial attack. The Riders had no idea if anyone had survived. The Trailways driver refused to continue, fearful of a similar fate.

Several white men stalked up the bus steps, demanding the front Black Riders retreat.

“You’re in Alabama, and n-----s ain’t worth nothing here,” one man said.

Charles Person took the first blow, a roundhouse right that rocked the 126-pound, 18-year-old college student. Two white Freedom Riders, 47-year-old CORE leader John Peck and 61-year-old professor Walter Bergman, rushed forward to shield the young Riders. Enraged at what they saw as white complicity, the assailants brutally turned on the older men.

Peck was thrown into the aisle, blood pouring from his face and head. Bergman lay unconscious, his wife and fellow Rider Frances Bergman, 57, sobbing for the attackers to stop as one jumped on the professor’s chest.

Slipping through blood, the gang pulled the victims toward the back. The driver, satisfied the bus was re-segregated, agreed to continue the drive.

"You all don't worry about nothing,” a police officer nearby said. “I haven't seen nothing.”

In Birmingham, the Trailways passengers met another brutal Klan attack. Person and Peck, still nursing their Anniston wounds but determined to carry out their test, were badly beaten along with Bergman.

“Bergman promised to take care of me,” Person said. “But it looked like every time he tried to come to my rescue, he kept getting beat more and more and more.”

Trailways Riders stumbled into the night to seek safety from the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a prominent Birmingham minister and civil rights leader. Shuttlesworth simultaneously dispatched a convoy to evacuate the other Riders from an Anniston hospital, under threat from another growing mob.

Stunned Riders huddled in Birmingham homes that night as the Kennedy administration urged CORE to fly directly to New Orleans. Alabama Gov. John Patterson refused to guarantee state protection if the group chose to continue on the ground. The activists wanted to push forward but eventually agreed to fly on because of threats and a bus driver boycott.

Within hours, word spread of the Alabama attacks.

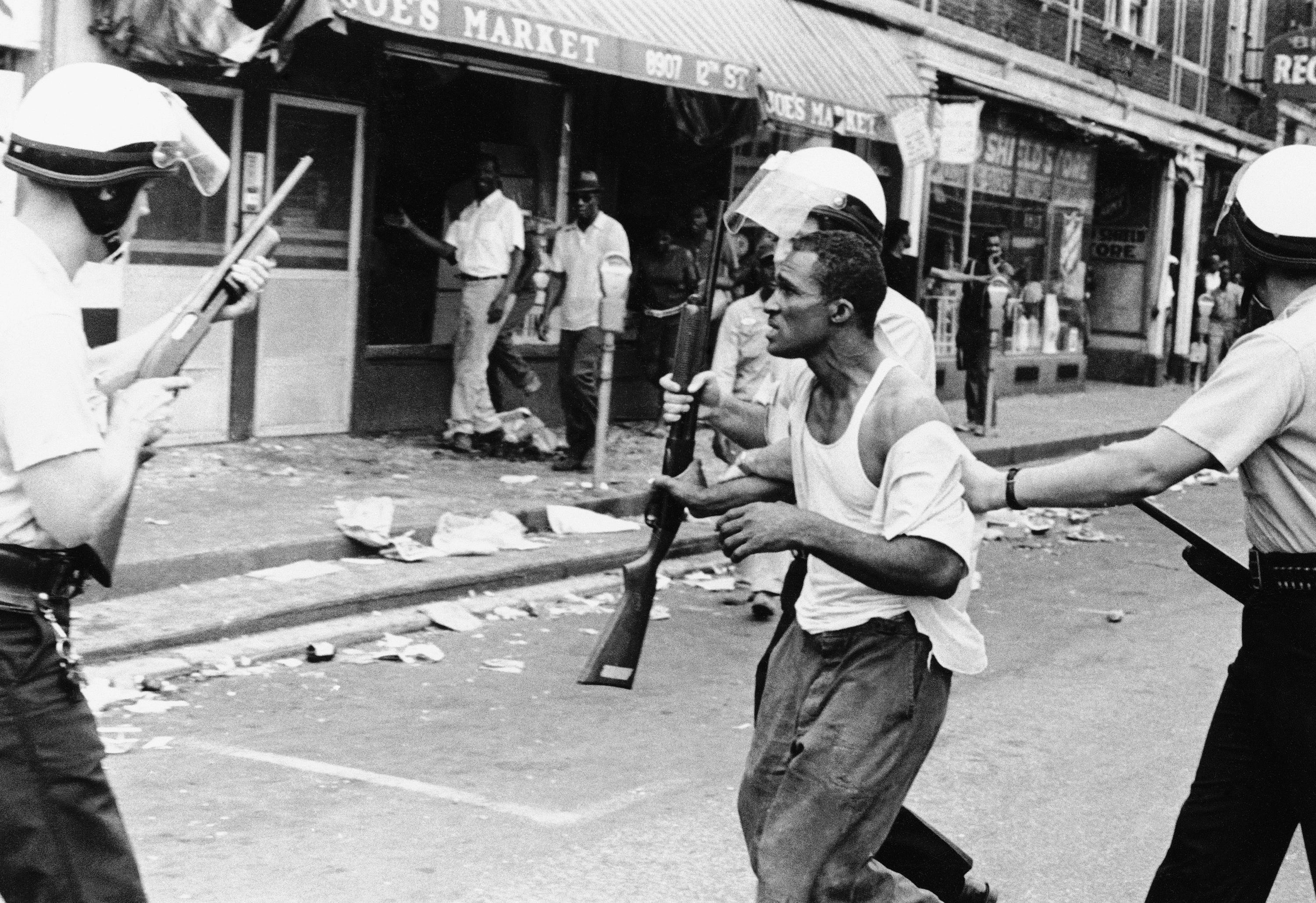

In Nashville, a group trained in nonviolence techniques rallied. Student leaders, including Lewis and civil rights strategist Diane Nash, organized teams, once deemed too young to participate, to pour into Alabama and Mississippi within 72 hours.

“They knew that something was going to happen to them,” Person said. “And yet, they came.”

More than 400 people faced violence and arrest through the early fall. The group adopted the “jail-no-bail” practice of refusing legal fines, a tactic developed earlier that year by Friendship Junior College students in Rock Hill, South Carolina, to financially pressure the court system. Many spent weeks inside Mississippi’s worst prison, enduring harassment and threats.

“They came by bus. They came by train. They came by air,” said Walker, of the Freedom Rides Museum. “You had this pressure of people, ordinary individuals who decided they were going to be part of this extraordinary effort to create change.”

Under pressure from the Kennedy administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission banned segregated facilities under its jurisdiction, effective Nov. 1. Test rides continued for months, but the removal of “Whites Only” signs across the South marked a significant, widespread victory for the movement.

“We didn’t know what was going to happen. We just knew we had to do something,” Person said. “With the sit-ins, it only affected that one city. You had to replicate your actions, over and over again. But with the Freedom Rides, once the edict was passed, it affected everybody, all at once.”

To report these stories, USA TODAY interviewed veterans of the civil rights movement, historians and witnesses and reviewed public records.

Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

"freedom" - Google News

October 04, 2021 at 07:20AM

https://ift.tt/3l56pKY

Freedom Riders traveled deep into the South in 1961. Klansmen beat them, then set their bus on fire. - USA TODAY

"freedom" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUAlgg

https://ift.tt/2VYSiKW

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Freedom Riders traveled deep into the South in 1961. Klansmen beat them, then set their bus on fire. - USA TODAY"

Post a Comment